The most romantic movies on Netflix are there when you need some summer lovin'! Get lost in the romance, the ups and downs of love and the vagaries of the world of dating, modern and ancient and be sure to have some tissues handy 'cos there's some weepies in the mix. When you're ready for the rollercoaster of romance or want to take a journey into the land of love, watch something from this list of romantic movies on Netflix.

(And if they aren't currently running, make a note for when they reappear in the schedule or find them elsewhere 🙂)

Thank you Pastemagazine.com for this awesome compilation.

Year: 2003

Maybe “Europudding” is a pejorative term for a reason, and maybe L’Auberge Espagnole is kinda the definition of Europudding. But the film is also a great case for the virtues of Europudding as an aesthetic, a frothy, lightweight flick that actually manages to find subtext in its continental blend of nationalities: It’s a casual statement piece about the benefits of multicultural contact, proof of how connecting with people who vibe with life differently than we do can change us for the better. It’s also sweet as hell without tasting treacly, a buoyant, joyful flick whose protagonist, uptight student Xavier (Romain Duris), is able to dodge his grim corporate future by heading off to Barcelona and staying in a house loaded with other, considerably less uptight students hailing from Italy, Belgium, England, Germany, Denmark, and Spain (obviously), who teach him how to unwind mostly just by passing through his orbit. You’re probably well-familiar with this kind of movie – “conventional career drone loosens up through socialization” is a pretty tried-and-true narrative framework, after all – but L’Auberge Espagnole has a breezy, unfussy earnestness that compliments its post-European Union identity.—A.C.

Year: 2015

When six friends reunite for a weekend at the beach, a relaxing getaway turns into an uninvited opportunity to deal with their emotional baggage. That’s Not Us follows three couples—one lesbian, one gay and one straight—during a presumably carefree weekend full of memories, intimate moments and exploration. Two have come to rekindle their sex life, while another couple grapples with how a prestigious grad program will force them hundreds of miles apart. For the third, the revelation that one of them doesn’t know how to ride a bike spurs a begrudging effort to grow together. But while the serene backdrop seems like the perfect place to soften the blows of their difficult issues, the tension that boils may be enough to end each relationship altogether. That’s Not Us is a fleeting and bare look into the lives of six twentysomethings as they fight growing older and growing apart to be the people—and couples—they fell in love with. —A.W.

Director: George Armitage

A slick combo of dark comedy, romance and ‘80s nostalgia, Grosse Pointe Blank is almost a partner to star John Cusack’s later film, High Fidelity. Both are about lonely men rethinking their direction in life set to a great soundtrack, but only in Grosse Pointe Blank does John Cusack play a hitman who murders Dan Aykroyd with a television. All that violence, and it still managed to capture the sweetness of returning home, and reconnecting with the one that got away/the one you left on prom night.—Garrett Martin and Shannon Houston

Director: Mélanie Laurent

Nothing’s more effective at shaking a teen out of their monotonous high school routine than the arrival of a new student. That’s the stuff actress/director Mélanie Laurent’s sophomore film, Breathe, is made of: mystery and allure, with generous dollops of adolescent rivalry, sexual awakening and verbal abuse spooned on top. Think of Breatheas a distant European cousin to the fraught teen movies of Larry Clark as well as Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen, stories of imperiled youth, loneliness and volatile sentiment. —A.C.

Director: Michael Mohan

A keen observation of the transition from artsy hipsterhood to responsible adulthood, Michael Mohan’s Save the Date examines the difficulties young adults face considering grown-up phases like marriage when half of their parents have divorced. With irrepressibly appealing performers playing flawed characters, he strikes a chord that resonates, even if some of the notes are a bit familiar. Lizzy Caplan (Bachelorette) stars as Sarah, a fiercely independent artist/bookstore manager who reluctantly agrees to move in with her adorable rocker boyfriend, Kevin (Geoffrey Arend). He’s so blissed-out about their new living arrangement that he’s completely tone-deaf to the fact that no, she wouldn’t appreciate being proposed to in front of all their friends (and a bunch of strangers, too) at the end of one of his packed shows. Key to the story and style of the film are Sarah’s ink drawings, created in real life by graphic novelist Jeffrey Brown, who co-wrote the screenplay. They serve as a creative window into Sarah’s soul while conveniently advancing the plot at a critical juncture.—Annlee Ellingson

Director: Rebecca Johnson

Based on a true and tragic story, Honeytrap tells the story of a young and naive teen from Trinidad, who moves to London to live with her mother for the first time since her childhood. We know Layla’s desire—desperation, really—to fit in with the Brixton crowd is going to end badly, but Jessica Sula’s portrayal makes the character’s seemingly simple-minded moves feel completely relatable. Not unlike the beautiful French film, Goodbye First Love, Honeytrap takes young love and its oft accompanying obliviousness very seriously. When Layla chooses the (ahem, wildly attractive) bad guy over the good guy, and finds herself unable to walk away from an abusive relationship, we can’t help but identify with her because writer/director Rebecca Johnson has taken care to show how Layla’s decision making is informed by both familial strains and a culture that celebrate hyper-masculinity. But it’s the end of the film that delivers a powerfully shocking blow—one that will make you wholly relieved that your days of teenage love are (hopefully) far behind.—Shannon M. Houston

Director: Lawrence Michael Levine

Flailing, waning coupledom sometimes resorts to practically anything to keep the romance alive: therapy, swinging, having a baby. Why not a murder mystery? A heart-on-sleeve ode to screwball comedies with a dash of Hitchcockian intrigue, Wild Canaries grounds some seriously dark hijinks in the anxiety and selfishness of a couple’s impending nuptials, using their fears of spending their lives with another insecure, difficult person to map out just how out of their depths they are in this whole real-life thriller scenario—or just how much romance needs a spirit of adventure and spontaneity to stay alive. It helps too that actors like Alia Shawkat, Kevin Corrigan and Jason Ritter are on hand, willing to lean in hard on such a caper, while director Lawrence Michael Levine (who stars with his partner Sophia Takal as the leading duo) somehow seamlessly blends his many genre touchstones with his origins in mumblecore, lending the antics some broad physical comedy in the process. The gag in which he, panic-stricken, slowly reclines the seat in his car in order to avoid being detected on a stakeout is worth the run-time alone.—Dom Sinacola

Director: Daniel Ribeiro

Based on Daniel Ribeiro’s 2010 short I Don’t Want to Go Back Alone, the Brazilian drama The Way He Looks (Hoje Eu Quero Voltar Sozinho) follows one teen’s ingenious coming-of-age story. Consistency is at the center of Leo’s world, from weekly visits with his grandmother to the walk home from school with his best friend, Giovana. That’s because Leo is blind, a condition that makes adapting to unforeseen changes difficult. As the high schooler’s desire for self-sufficiency grows, his behavior begins to confuse and alienate those closest to him. Much of that growing disconnect stems from his new friendship with Gabriel, a boy whose innocent insensitivity towards Leo’s visual impairment forces the shy teen out of a stifling routine. Ribeiro’s exploration of the experiences that catapult us through the complicated throes of teenhood is at times subtle, but always grounded and ultimately the film’s greatest strength. When and how do we become independent from our parents? What type of verbal or physical commitments does a relationship require? Where is the line between friendship and something more? And most interestingly, what does it say about the biology of sexuality, and the chemistry of love, when you can’t see the person you’re attracted to? The Way He Looks is no traditional tale of growing up. It’s a tender illustration of the coming out we all experience as we cross the threshold of young adulthood.—Abbey White

Director: Bharat Nalluri

A stylized study on the ageless paradox of suddenly finding oneself in fortunate circumstances, Miss Pettigrew Lives For A Day features Frances McDormand as the title character, an out-of-work nanny suddenly thrust into the glamorous existence of Delysia Lafosse (Amy Adams), a blossoming West End actress in 1939 London. Lafosse requires a social secretary to sort out the impending mess of her love life, at least until she can land the lead in a new musical being produced by one of her current paramours. Miss Pettigrew must navigate the nasty waters between the haves and have-nots, who are all rather deceptively mixed together in the upper-crust theater scene. Only two or three twists of McDormand’s wizened countenance are required to let us know that all is not as it seems; in the end, the characters’ integrity is the only virtue that cuts the smoke of the flash pots.—David Mead

Director: Lorene Scafaria

Released in mid-summer of last year, director Lorene Scafaria’s (Nick and Norah’s Infinite Playlist) feature film directorial debut came and went without much fanfare. To be fair, it was a hard sell. An apocalypse comedy/rom-com/road trip movie starring the likes of Steve Carell and Keira Knightley, two actors who don’t seem like they belong in the same world together let alone in a romantic pairing, the movie was never going to be a runaway hit. It’s certainly not without its flaws, with a tone that oscillates sharply between comedy and drama. And yet, Carell and Knightley’s combined charm and chemistry make this one end-of-the-world road trip worth checking out.—Dan Kaufman

**Director: **Joe Swanberg

If you feel compelled to go full indie and can’t stand love stories with tidy, happy endings, Drinking Buddies should be your pick. It’s an unconventional romance in that most of the characters never commit to the relationships or infidelities we expect them to. Instead, it’s about temptation, the lies we tell ourselves in a relationship and the boundaries between friendship and romantic feelings. A scion of—but not full-fledged entry into—the mumblecore genre, its largely improvised dialog lends an air of reality to the conversations, but those expecting typical genre conventions may find themselves perplexed when you don’t get anything resembling the “wedding bells” ending of the typical romantic comedy.—Jim Vorel

Director: Dan Mazer

Wile many romantic comedies ending at the alter, Dan Mazer’s British film I Give It a Year begins there. After a whirlwind romance, Nat (Rose Byrne) and Josh (Rafe Spall) get married, much to the dismay of their friends. Problems arise immediately, and the film is structured between a marriage counselor’s office and flashbacks of their squabbles. On the surface it’s an anti-rom-com, but it’s also a frank look at a couple committed to at least giving the marriage a go when even as it’s attacked from all sides.

Director: Lynn Shelton

Leave it to Lynn Shelton, one of America’s most exciting emerging filmmakers, to take the old formula of “put a few people in an isolated cabin and let them talk it out” and make it into a fascinating film. She’s helped greatly by three very strong lead performances — from Rosemarie Dewitt, Emily Blunt, and especially Mark Duplass. The dialogue hovers in that intriguing space between scripted and improvised, and the film walks the tightrope expertly.—Michael Dunaway

Year: 2011

In the oddly raunchy and thoroughly satisfying septuagenarian lesbian road film Cloudburst, Oscar winners Olympia Dukakis and Brenda Fricker star as Stella and Dot, a lesbian couple who have spent the last 30 years living the classically Sapphic good life on the rugged coast of Maine. After Dot gets put into a nursing home by her uptight granddaughter, her lover breaks her out and instead takes her on a road trip, promising, “We’ll drive to Canada and then we can get legally married and no one can separate us.”

The film suffers moments of significant clumsiness, including distractingly sitcomy one-liners. But the open road serves as a brilliant palette for writer-director Thom Fitzgerald to take scenic advantage of rolling hills and ocean. Nature itself becomes a key character in the film. The titular cloudburst, which drenches Stella and Dot in a moment of deep love and devotion to one another, serves as a sort of simultaneous protagonist and antagonist, celebrating and troubling the lovers at the same time.

Cloudburst is easily one of the most polarizing films on this list. The idea of cowboy hat-clad lesbian retirees on the open road, pontificating about the power of a certain C word and cracking off-color jokes to a handsome hitchhiker (Ryan Doucette), is likely either immediately intriguing to a given viewer or laughably off-putting. Yet at its best, the film provides a venue for two revered talents to thoroughly buck the stereotypical roles available for older actresses and showcase the nuance and verve of their craft. —N.M.

Director: Julie Delpy

A matchless New York romantic comedy with language full of smarts and crudeness, 2 Days in New York brings audiences a hilarious 48-hour portrait of an atypical modern family. Julie Delpy’s intellect and talent as a writer/director/actress are undeniable, leaving one to wonder why she doesn’t participate in this Hollywood juggling act more often. In a season where critics and audiences continue to praise comedic female writing and directing, Julie Delpy should receive nothing less than a standing ovation for 2 Days in New York, a lively example of sharp and entertaining filmmaking.—Caitlin Colford

Director: Peter Howitt

An inventive charmer from England, Sliding Doors grafts the rom-com treatment onto the philosophical notion of the “butterfly effect,” which asserts that the smallest incidents can have a profound impact on one’s life. In the case of the film, this defining moment is a young woman’s s attempt to catch a train. From here, her life splinters into two parallel realities—one in which she catches the train and discovers her boyfriend’s infidelity and one in which she misses her ride and remains oblivious to his indiscretions. While much of the film’s energy goes into servicing this complex gimmick, it’s the sharp writing and charming performances from the likes of Gwyneth Paltrow, John Hannah and John Lynch that keeps this from merely feeling like a needless exercise in story structure. —Mark Rozeman

Director: Hany Abu-Assad

More trenchant as a political allegory than a character drama, Omar is more interested in the ideas within this slow-burn thriller than in plot machinations. To writer-director Hany Abu-Assad, maniacal twists and cunning action set pieces would simply get in the way—better that we spend our time thinking about why the characters find themselves in this situation at all. Nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, Omar stars Adam Bakri as the titular young Palestinian, who must daily scale the imposingly tall security wall that separates him from his girlfriend, Nadia (Leem Lubany). Though very much in love, they haven’t yet revealed their relationship to her brother (and Omar’s good friend) Tarek (Eyad Hourani), who is planning with Omar and another close pal, Amjad (Samer Bisharat), to kill an Israeli soldier. The three friends’ mission is a success—it’s Amjad who pulls the trigger—but soon after, Omar is snagged by Israeli forces, led by Agent Rami (Waleed F. Zuaiter). Threatening Omar with imprisonment, Rami promises him freedom if he’ll deliver Tarek, the group’s leader, to them in exchange. What’s most resonant in Omar is that, just as we can’t always gauge the characters, they’re, too, concealing parts of themselves from each other, a byproduct of living in a part of the world where distrust is commonplace and secrecy a necessity. Which is why Omar’s startling ending is both somewhat mystifying and also oddly perfect—we don’t see it coming, and yet deep down, we’re not surprised at all that it happened.—Tim Grierson

Year: 2014

The biographical drama Reaching for the Moon depicts the life and love of Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Elizabeth Bishop (Miranda Otto) and her partner, Lota de Macedo Soares (Glória Pires). From their first meeting to their last, Bruno Barreto captures the tumultuous and sensuous love affair between the American poet and Brazilian architect, as well the addictions that addled both artists—especially their addictions to each another. The film captures the perpetual unsteadiness of a complicated romance, but outside of its ability to dramatize one of queer history’s most remembered and unconventional relationships, it perfectly encapsulates the all-consuming power of love. Both women, a dichotomous pair from the beginning, are driven by their artistic visions. It’s that creativity that serves as the major force behind their mutual enchantment. Unfortunately, their equally controlling and codependent natures get the best of them. The outlets they turn to are only temporary releases for issues neither is willing to address. As Lota and Elizabeth lean on their respective crutches to stay afloat in a whirlwind romance, jealousy, a third partner and their unpleasant pasts create hurdles that are ultimately too much for them to bear—whether together or apart. —A.W.

Director: Alex Lehmann

Sarah Paulson is one of the most vital actors working today, and at this particular moment she’s damn close to ubiquitous; here she shows up as one of two leads in newcomer Alex Lehmann’s lovely romantic comedy Blue Jay, a compact and unassuming film about big, life-changing things that’s presented in a beautiful monochrome package. Think of it as a palate cleanser for Paulson after a year spent maneuvering productions of grander scope and ambition. But scale and quality exist in two separate zip codes, and what Blue Jay lacks in import it makes up for with effervescence and melancholy. As though to put Paulson’s luminous talents to the test, Lehmann has cast her alongside Mark Duplass, a man primarily known for making tons of low-fi mutter-fests and whose range allows him comfortably to play himself. Paulson and Duplass make such a great pair that the film’s relative nothingness is pleasurable rather than painful. Blue Jay only clocks in at about an hour and twenty minutes (less, counting the credits scrawl), so it should breeze along by its very nature, but it feels like it only runs about half as long as that. It’s well crafted, well mannered and very well acted, though you may decide for yourself if all credit should go to Paulson. She draws out Duplass’ best merits as an actor, much as Amanda draws out the best in Jim: The more the film progresses, the brighter and more enthusiastic Duplass becomes, relishing every second he gets to be on screen with her. Their chemistry is palpable.—Andy Crump

Director: Mike Birbiglia

Charlie Chaplin once said, “To truly laugh, you must be able to take your pain and play with it.” Mike Birbiglia takes the pain of a struggling comic, an unsure boyfriend and a scared sleep-disorder patient, and plays with these mounting problems for our amusement. Not many sleep-disorder stories—even those first shared with Ira Glass on This American Life—have ever been as funny as Birbiglia’s.—Monica Castillo

Director: Walter Lang

Of the nine movies Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy made together, Desk Set may not be the most well-known, but the 1957 romantic comedy was almost shockingly ahead of its time. Hepburn’s Bunny Watson is the head of the research department at the Federal Broadcasting Network, a career woman in a position of power who’s shown in many instances throughout the movie to be damn good at her job. When Tracy’s Richard Sumner, an efficiency expert, shows up to evaluate how the department would function with a computer (in 1957!), he and Bunny predictably butt heads, but their chemistry is undeniable (aided obviously by the fact that Hepburn and Tracy had a 26-year relationship in real life). It’s hard to believe that a movie about a woman whose work comes first, that stars a 50-year-old actress,actually passes the Bechdel test and prominently features a computer was actually made in 1957, but we’re so glad it was.—Bonnie Stiernberg

Director: Greg Mottola

Adventureland is a part of a long tradition of autobiographical coming-of-age stories. It’s reasonable to assume these stories remain so popular because they’re personal to filmmakers, but curiously, the actual movies are almost all the same—quirky caricatures of youth spliced with the usual awkward rites and first loves. Together they create a fantasy of shared adolescent experience that’s easy to embrace, especially since it usually ends with a smooth welcome into the future. Adventureland does not break from this, and yet it feels special—light, easy to like and more forthright than one would expect. Set in 1987, when writer-director Greg Mottola was the same age as the characters, the movie considers James (Jesse Eisenberg), a recent college grad whose plans for a European summer morph into a season at the eponymous local park. The stock population is all there: the unhinged boss (Bill Hader), the nerdy sage (Martin Starr) and, of course, the kindred soul (Kristen Stewart). Booze, hash brownies, malicious elders and romantic entanglements complicate things, but not by much. Mottola made Superbad, a very funny movie that became a phenomenon, but he insists on a more modest approach here. The movie works harder to suggest a mood than it does to get laughs, and that’s no small thing, especially since its writer-director spent a decade under the influence of Judd Apatow. On the way out of Adventureland, there may not be any eminently quotable lines or gags, but there is the rare sense of satisfaction that comes from a story told through careful, patient eyes.—Jeffrey Bloomer

Director: Miranda July

Not a single character in Me and You and Everyone We Know acts his age. A father lights his hand on fire to glean smiles from his kids. A fat, middle-aged nobody pens horny notes to teenage girls on his living room window and timidly ducks out of frame. And a little girl stores dishes and dolls in a war chest as her future husband’s dowry. The film is a romantic dramedy set between a lowly shoe salesman (John Hawkes) and a fledgling video artist/cab driver for the elderly (Miranda July). Thrown into the mix are a slew of other deviants. Amazingly, first-time feature director, writer and lead Miranda July treats these offbeat behaviors with a puzzling familiarity. Borrowing from her background in multimedia art, she’s created a weirdly comfortable film for mixed audiences. It’s a quirky precursor to a significant crossover career in cinematic magical realism.—Cameron Bird

Director: Andrew Haigh

Weekend is a quiet, well-executed study of a relationship’s first-bloom. But since it’s a tale of boy meets boy instead of boy meets girl (or meets aliens, or really cool weapons, or, best of all, aliens that can turn into really cool weapons!), Andrew Haigh’s film is a gem that’s destined to garner little attention outside of Netflix's Gay & Lesbian genre section. The plot is simple. Russell (Tom Cullen) goes out on a Friday, first to a friend’s house and then to a gay bar. He brings Glen (Chris New) home with him. They hook up. Over the next two days, the two men take the first steps in that orientation-immune dance in which we all participate. Is this something special? And if so, for a moment or a day? For longer? Ultimately, Weekend reminds its viewers that homosexual couples fall in love in much the same way as heterosexual ones: with careful restraint and bursts of joy, with nagging doubts and tentative hopes, and with the desire to connect at odds with the fear of being hurt.—Michael Burgin

Year: 2007

Sex, gender and orientation collide in writer-director Lucía Puenzo’s XXY. The 2007 Argentine-Spanish-French drama follows Alex, a 15-year-old intersex teen who is living as a girl. When Alex decides to stop taking her strict hormone regimen, her parents worry that her more masculine traits will resurface, revealing Alex’s true sex. In an attempt to save his child from society’s prying eyes, Alex’s father moves his family to a small seaside village in Uruguay. But her mother, Suli, takes things a step further. Without Alex or her father’s knowledge, Suli invites an Argentinian surgeon and his family to discuss the possibility of gender reassignment surgery. Upon their arrival, Alex meets the surgeon’s son, Álvaro, and embarks on a painful and liberating journey of sexual and personal identity.

At the core of Puenzo’s film is a story about the emotional and physical intricacies of young love. Underneath that lies both teens’ desperate need to understand what attracts them to the other. Alex and Álvaro must grapple with what they feel for one another amid a larger conversation about sex, gender presentation and cultural conformity. As a result, viewers get a messy, fraught portrait of our convoluted ideas of sexual identity. While Álvaro’s father fears he is gay and Alex is ostracized for having male and female biological parts, it’s not their differences but rather their community’s fear of the unknown that makes them targets of hostility. Alex’s gender and experience defies conventions, much in the same way her unraveling sexuality does. The teen’s journey reminds us our sexual identity is just as much about the way someone makes our heart feel as it is our physical response to them. XXY is not just a coming-of-age or self-acceptance story, but a deeply thoughtful expression of the lengths we go to in understanding our own emotions and bodies. —A.W.

Year: 2015

Taiwanese director Anucha Boonyawatana’s first feature is a hauntingly romantic tale of forbidden love and the dark secrets we keep in its name. After Tam (Atthaphan Poonsawas), tormented by his classmates and abused by his family, meets the attractive boy Phum (Oabnithi Wiwattanawarang) in the quiet corridors of a supposedly haunted swimming pool, his life takes a somewhat poetic turn. The open expression of their love is confined to the decaying walls of the abandoned building, but the isolation of the space helps build a strong sense of trust and courage between them. Yet what begins as an exciting new romance quickly turns bleak when Phum reveals aggressive plans to get his family’s now trash-covered land back from those who stole it. As Tam becomes more intertwined with Phum’s plot, the lines between what’s real and what’s not become blurred, forcing the young man to choose between equally harrowing realities.

If you’re looking for a movie that gives you answers for all your burning questions, The Blue Hour isn’t for you. But in spite of its somewhat disappointing opacity, Boonyawatana’s film features a strong use of horror as a metaphor for our worst idealizations. Narratively and visually, The Blue Hour is true to its name. The film is dark—from themes and dialogue to settings and lighting—but it’s all delivered, rather intriguingly, on a canvas of burgeoning and desperate love. This careful storytelling approach proves that Boonyawatana’s goal isn’t to simply explore the naiveté of youth and the heartbreak of romance. Instead, The Blue Hour demonstrates the unworldly nature of our firsts and lasts, and the rot of time that often accompanies our greatest desires. —A.W.

Director: Josh Radnor

Best known for playing Ted on the hit sitcom How I Met Your Mother, Josh Radnor is establishing himself as a thoughtful writer-director of feature films dealing with young adults facing—and embracing—adulthood. An ode to his years at Kenyon College specifically and liberal arts education generally, Liberal Arts is at once a profound defense of academia for academia’s sake and a gentle critique of nostalgia: Live too much in the past (or in a book), and you’ll miss out on what’s in front of you. Jesse (Radnor), a college admissions counselor in New York City, is confronted with these realities when he’s invited to return to his Ohio alma mater to give a speech at a retirement party for his favorite English professor, Peter (Richard Jenkins). Newly single and weary of dealing with life in the big city (his laundry is stolen from the Laundromat in the opening scenes of the film), Jesse literally walks with a spring in his step when he gets back on campus. There he meets Zibby (a luminous Elizabeth Olsen), a sophomore with a passion for classical music, improv and trashy vampire novels. In a series of conversations about books, music and theater, they connect. As their relationship develops, however, their age difference and the perhaps unhealthy nostalgia behind their burgeoning romance start to weigh on Jesse. In his films, Radnor tends to present a thesis and then hammer away at it. In this case, it’s saying yes to whatever life puts in front of you.—Annlee Ellingson

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

But really—he didn’t do it.

Cary Grant plays John Robie, a retired jewel thief who’s enjoying his golden years tending vines on the French Riviera. But just when the Grenache is hitting the perfect Brix level, a series of copycat heists put Robie back in the thiefly limelight. Seeking to clear things up, he compiles a list of locals who are known to have heist-able jewels, and being a smart and wily guy, he starts tailing an especially pretty one (Francie, played by Grace Kelly). Budding romance can be an accidental side-effect of these things, but when Francie’s ice does go missing, she suspects John and it sours their relationship, as one might expect. John goes on the proverbial lam to get to the bottom of it. Talk about jewels! Nothing ever sparkled quite like Cary Grant and Grace Kelly onscreen together, especially with the legendary Edith Head on costume design—and their peerless charisma is in amazing hands here. The film itself is a bauble, and unapologetically so. It’s light and frothy and absolutely not Rear Window, not that that’s an indictment. Sometimes it’s enough for something to simply be charming and beautiful. This film proves it. —A.G.

Year: 2011

The first feature by Spike Lee protégé Dee Rees tells the story of teenager Alike (Adepero Oduye), a dutiful and accomplished daughter from a religious household in Brooklyn. As Alike struggles to find a proper expression of her sexuality, she follows her out friend Laura (Pernell Walker) into a scene of African-American lesbians whose brash liveliness proves a bit unsettling. When Alike’s mother introduces her to Bina (Aasha Davis), Alike contends with both her own sexuality and the ways that her identity ties her to a community she doesn’t quite fit in with.

Shot in Brooklyn in a vivid palette of deep primary colors, Pariah is evocative of Spike Lee at his best. However, in content, the film is distinctive in its engagement with characters who seek to belong. Eschewing both hipster navel-gazing and pat clichés, Pariah instead lets its characters exist in a beautiful human ambiguity, on the edge of society but also finding their own place at that edge. The result is a thought-provoking and thoroughly entertaining addition to the canon of modern queer film. —N.M.

Director: Barry Jenkins

Before Wyatt Cenac rose to prominence as one of The Daily Show’s funniest, sharpest correspondents, he starred in 2008’s Medicine for Melancholy, a touching, just-right drama about two strangers who wake up in bed after drunkenly hooking up the night before, deciding that they’ll spend the day hanging out and getting to know one another. The feature debut of Moonlightwriter-director Barry Jenkins, this modest indie gem is highlighted by its terrific lead performances—Cenac as the charming, thoughtful Micah and Tracey Heggins as the alluring, hesitant Jo’—but also by Jenkins’ quiet portrait of contemporary urban African-American life. Medicine for Melancholy is about our nervous desire to connect with another person but, just importantly, it studies how issues of race and gender seep into every experience, even love.—Tim Grierson

Year: 2014

Shot entirely with an iPhone, Sean Baker’s Tangerine is a near perfect execution of raw realism juxtaposed against fleeting yet profound moments of human vulnerability and tenderness. Writer-director Baker wastes no time flinging viewers into his story’s cacophonous premise: a delirious misadventure focusing on the fractured but luminous lives of transgender prostitutes Sin-Dee Rella (Kitana Kiki Rodriguez) and Alexandra (Mya Taylor). Such immediacy helps set up the fast-paced, heartfelt journey that follows. When Sin-Dee Rella and Alexandra reunite following the former’s release from her month-long prison sentence, we learn that Sin-Dee’s boyfriend and pimp Chester has been seeing another woman. The news ignites a nearly two-hour chase around the streets of L.A. to locate and handle the “issue.”

Within the story’s backdrop of the wild and dingy Los Angeles cityscape, Tangerine’s rule-defying characters thrive. Though it could easily devolve into an exploitative revenge porn drama, Tangerine shirks its expectations, becoming an aggressive examination of human complexity and a bold refusal to judge a book by its cover. That goes not only for its approach to characterization, but just about every narrative aspect of the work—from the way Baker develops his larger plot to how he sequences his shots. This tale carefully upholds its characters’ sharply divisive existence. The deeper we go into the world of these two sex workers, the more we forget our assumptions of those who inhabit it. In the end, Tangerine is about discovering that our roughest edges can be both our most colorful and meaningful.—Abbey White

Director: Woody Allen

Late-era Woody has been an interesting phenomenon to watch, as his occasional hits and stupefying misses come hard on each other’s heels. Midnight in Paris is a heady love story, but more importantly is also an exploration of nostalgia, the artistic impulse, and even happiness itself. It’s an entertaining and sometimes hilarious film that belongs squarely in Allen’s “hit” column. Rachel McAdams’ natural (and considerable) charm and charisma are a perfect counterpoint to her character, who in her unlikeability actually recalls Billy Zane’s ridiculous cad in Titanic. Michael Sheen is a different kind of cad—the pedantic know-it-all that is so fun to hate that it’d be a shame to give him any redeeming qualities. Other standout performances are turned in by Marion Cotillard, Kathy Bates, and Corey Stoll in a pitch-perfect career turn. And against all odds, Owen Wilson turns out to be an excellent choice for the Allen-esque protagonist (Woody, of course, seldom writes any other type). Wilson seems to project a goofy thoughtfulness naturally, and it softens the edges of Allen’s neurotic writing and draws the viewer in. Unlike many of Allen’s protagonists, we’re really rooting for Gil. Combine that with a daring concept, a charming supporting cast, and some classic Allen zingers, and you’ve got an ideal summer confection for the film-buff set.—Michael Dunaway

Director: Kevin Smith

Anyone who has listened to enough hours of Kevin Smith’s podcasts or lengthy Q&A sessions knows that, behind his perpetual potty-mouth and flashes of egomania, Smith is a big softie at heart. After two films that reveled in crass slackerdom lifestyles (Clerks and Mallrats), Smith honed his writing voice for his third feature, Chasing Amy. The film stars Ben Affleck as an amateur comic book artist named Holden whose life is thrown awry when he meets a beautiful and vibrant girl named Alyssa (played by Smith’s then-girlfriend Joey Lauren Adams) and instantly falls in love. The problem? Alyssa is a lesbian. Crushed but still determined to spend time with her, Holden develops a close friendship with Alyssa, eventually telling her how he feels with the kind of speech that anyone who has ever experienced a hurtful bout of unrequited love has tossed around in their minds but never found the words to express.—Mark Rozeman

Director: Ava DuVernay

In 2012, a mostly unknown Ava DuVernay became the first black woman to win Best Director at Sundance for her film Middle of Nowhere. It’s a tender drama featuring a predominantly African American cast. DuVernay grew up in South Central Los Angeles, and the particulars of the story were drawn from a situation she saw all too much growing up—a story of a couple separated due to incarceration. “Being from Compton I really watched firsthand so many women struggling with incarceration and the victimization of that, from their perspective,” she told Paste when the film was released. “So, that all got added into the stew of the screenplay.” The powerful lead performance comes courtesy of Emayatzy Corinealdi. She lent a striking vulnerability to her first lead role.—Michael Dunaway

Director: Richard Curtis

When it comes to portraying love confessions of all varieties, very few can beat the kind on display in Richard Curtis’ epic romantic comedy Love Actually. In one of the many romantic threads, Juliet (Keira Knightley), a recently married woman, has just discovered that her husband’s best friend Mark (Andrew Lincoln) has been nursing a secret crush on her. One night, he arrives at their front door and silently delivers his long repressed feelings via hand-drawn cue cards. While certainly sweet and heart-warming, the inherent sadness that pervades this scenario—such a relationship can never work out between the two—prevents the exchange from being overly saccharine. —Mark Rozeman

Director: Joe Wright

Keira Knightley is characteristically exquisite—physically, yes, but also emotionally—subtly conveying a rising heat that can’t be expressed. As Anna, her unraveling is moving in its hysteria. The movement among production designer Sarah Greenwood’s sets—Moscow and St. Petersburg, the city and country—is kinetic and fluid, and Wright’s concept is visually and intellectually stimulating… an esoteric exercise that explores the intersection of literature, theater and cinema—at once challenging and rapturous.—Annlee Ellingson

Director: Alfonso Cuarón

A road trip along the coast of Mexico turns out to be one of sexual discovery for two punk teenagers (Gael Garcia Bernal and Diego Luna). Meanwhile, the trip turns out to be the bittersweet final adventure for their older female companion (Maribel Verdu), as she struggles with a life full of regret and roads not yet traveled. Y Tu Mama Tambien is at times playful and seductive, but slowly reveals itself to be a substantive dual story involving both coming-of-age and coming-to-terms. —J. Medina

Director: Abdellatif Kechiche

Three-hour movies usually are the terrain of Westerns, period epics or sweeping, tragic romances. They don’t tend to be intimate character pieces, but Blue Is the Warmest Color (La Vie D’Adèle Chapitres 1 et 2) more than justifies its length. A beautiful, wise, erotic, devastating love story, this tale of a young lesbian couple’s beginning, middle and possible end utilizes its running time to give us a full sense of two individuals growing together and apart over the course of years. It hurts like real life, yet leaves you enraptured by its power. —T.G.

Director: Shane Carruth

Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color builds a stunning mosaic of lives overwhelmed by decisions outside their control, of people who don’t understand the impulses that rule their lives. Told with stylistic bravado and minimal dialogue (none in the last 30 minutes), the film continually finds new ways to evoke unexpected feelings. The visuals—from underwater schist to microscopic photography—combine with extraordinary sound design and rhythmic cross-cutting to create a hypnotic portrait of the story’s intertwined lives. The means to the interconnectivity is a small worm whose parasitic endeavors link lives together. But Carruth doesn’t bother with expository sci-fi gibberish. The organism does what it does, and that’s all we need to know. This allows more time to explore the emotional impact the organism has on the characters. Ultimately, that’s where Upstream Color succeeds. An elaborate intellectual concept fuels the film, but a rich sense of humanity gives it power. —Jeremy Matthews

Director: Mike Mills

Beginners is directed by Mike Mills, who hasn’t made a feature film since 2005’s Thumbsucker. And this time, Mills drew on his own life for the story of Beginners. Like Hal, Mills’ father also came out of the closet after the death of his mother. Cancer took both of his parents and there’s a subtle jab at smoking in the film. But Beginners is not a message movie; it’s an ambitious play on coming-of-age late in life, of course for Hal but also very much for Oliver, and perhaps for Mills himself. —Jonathan Hickman

Director: John Huston

The madcap, screwball comedies of the ‘30s and ‘40s helped set the template for the battle-of-the-sexes comedies that would populate American cinemas for years to come (and still do, to some extent). Writer/director John Huston’s genius in making The African Queen was taking the feuding couple out of the metropolitan areas for which they’d often been associated with and instead placing them square in the middle of an inhospitable jungle. With the added element of survival driving their journey, the flirtatious banter between classy widow Rose Sayer (Katherine Hepburn) and crass boatman Charlie Allnut (Humphrey Bogart) crackles all the more, making for a rom-com as vicious as it is sweet. —M.R.

Director: Gus Van Sant

The story of a genius janitor capable of solving the world’s most difficult mathematical problems, Will is both exasperating and loveable as the Boston boy reluctant to live up to his true potential. Robbin Williams takes the oft-clichéd mentor paradigm and turns it into a wholly original character as Damon’s therapist Sean. But what’s special about this film is the way Gus Van Sant captures the existential angst and, ultimately, the frustrated striving of a brilliant boy form the wrong side of the tracks. Matt Damon and Ben Afleck star in their own breakthrough roles as best friends closer than even blood brothers. Though the movie touches on heart-wrenching topics like childhood abuse and heartbreak, the sarcastic humor and witty banter are just as memorable. Effortlessly charming and never overwrought. —Amy Libby

Director: Sharon Maguire

Diehards may have been initially miffed at her casting, but Renée Zellweger was crucial to the movie’s success. She’s boundlessly charming as Bridget Jones, gaining 20 pounds to play the British singleton who falls for Hugh Grant and (eventually) Colin Firth. From her appalling bad public speeches to lip-synching to Sad FM songs in her pajamas, Zellweger carries the film on her (still slender) shoulders. —J. Medina

Director: John Carney

Sing Street spins art out of history, but you might mistake it for pop sensationalism at first glance. If so, you’re forgiven. In sharp contrast to John Carney’s breakout movie, 2007’s sterling adult musical Onceegin Again, Sing Street aims to please crowds and overburden tear ducts. There’s a sugary surface buoyancy to the film that helps the darkness clouding beneath its exterior go down more easily. Here, look at the plot synopsis: A teenage boy living in Dublin’s inner city in 1985 moves to a new school, falls in love with a girl, and forms a band for the sole purpose of winning her over. If the period Carney uses as his storytelling backdrop doesn’t make Sing Street an ’80s movie, then the mechanics of its story certainly do. You may walk into the film expecting to be delighted and amused. The film won’t let you down in either regard, but it’ll rob you of your breath, too.—A.C.

Director: John Madden

Another film whose reputation has suffered somewhat since its initial reception, largely in this case as a result of an ill-considered Oscar and Gwyneth Paltrow’s ill-considered management of her public persona since then. No one is more annoyed with latter-day Goop than me, but even I can admit that Shakespeare in Love gets a bad rap. It’s delightful, especially for those with any experience in the theater whatsoever (the theater world itself is the romantic interest of the film, every bit as much as Gwyneth’s Viola de Lesseps). And, it’s now safe to say out loud – Ben Affleck is fantastically charming in this film. If you haven’t seen it in awhile, you’ll be surprised at how much more you like it than you remembered.—Michael Dunaway

Director: Otto Preminger

Maybe falling in love with dead people is just an occupational hazard of being an investigative detective in New York City. Then again, maybe a shotgun blast to the face couldn’t keep anybody from developing a crush on Gene Tierney, which is pretty much how the plot of Otto Preminger’s Laura goes. The film tracks the trajectory of NYPD detective Mark McPherson’s growing obsession with the eponymous young lady as he cobbles together the bits and pieces of her life and death. Poring over her diary and her letters, he comes to moon over her, and why not? She’s every bit as delightful as Preminger’s movie. Laura doesn’t waste time and stacks contrivance on top of unlikelihood, but such is the strength of Preminger’s craft and the performances of his cast that the film’s convolution doesn’t matter.—A.C.

Director: Mike Nichols

In the undisputed king of movies for those headed out into the real world, a hyper-accomplished recent grad (Dustin Hoffman) panics at the prospect of his future and falls into an affair with the much older wife of his father’s business partner (Anne Bancroft). It helped define a generation long since embalmed by history, but the sense of longing for an alternative hasn’t aged. —Jeffrey Bloomer

Director: Rob Reiner

Quite possibly the most perfectly executed transformation of a beloved book to a beloved film in the history of the sport. A family-friendly “kissing movie” with pitch-perfect performances by the entire cast—from main character to bit player—The Princess Bride is the most relentlessly quotable film anywhere this side of Monty Python and their Holy Grail. Though regarded warmly enough by critics, its status as comedic fable ensures it is criminally underrated on most lists. Inconceivable? Alas, no. But unfair, nonetheless. —M.B.

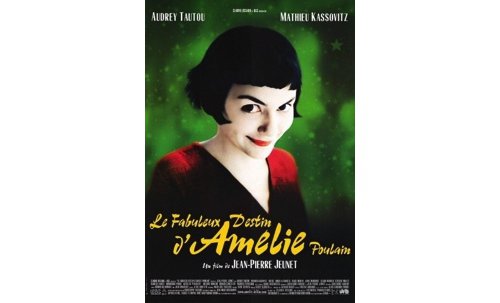

Director: Jean-Pierre Jeunet

A delicate, delicious little French trifle, Amélie is easily one of the most romantic films on Netflix. The adorable Audrey Tautou launched herself into the American consciousness as the quirky do-gooder waitress who sends her secret crush photos and riddles masking her identity in order to make their first encounter—and first kiss—the most romantic moment of her life. Endlessly imaginative and beautifully photographed, Amélie is a film to be treasured. —J. Medina

Director: Wes Anderson

Anderson and co-writer Roman Coppola avoid clichés at every opportunity. The forces that would typically work to tear Sam and Suzy apart instead rally behind them, perhaps infected by the conviction of their love, which never wavers, even in argument: “I love you, but you don’t know what you’re talking about.” Moonrise Kingdom is whimsical and, yes, precious, but it is so in the very best sense of the word. —A.E.

Please rate this article

More